I. U.S. Trade Restrictions on China

The Biden administration made its mark on U.S. sanctions and export controls in 2021—reviewing, revising, maintaining, augmenting, and in some cases revoking various trade restrictive measures created during the Trump era.China remained at the forefront of the U.S. national security dialogue as the administration sought to solidify measures to protect U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data and blunt the development of China’s military capabilities after numerous earlier efforts by the Trump administration were blocked or limited by U.S. courts.China showed few signs of backing down in the face of U.S. pressure, instituting new restrictions that could potentially require multinational companies to choose between compliance with U.S. or Chinese law—creating a potential compliance minefield for global firms.

In October 2021, the U.S. Department of the Treasury published findings from its nine-month long review of the sanctions administered and enforced by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), setting forth a policy framework to guide the imposition of new sanctions.The principles articulated in that review were apparent in major sanctions developments throughout the year—including new targeted sanctions on Myanmar, Belarus, and Ethiopia; the issuance of general licenses to facilitate the flow of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover; termination of the sanctions with respect to the International Criminal Court; revocation of terrorist designations on the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (“FARC”) and the Yemen-based Houthis; and the first designation of a virtual currency exchange for its role in facilitating ransomware payments.Negotiations over the future of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”)—the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement abandoned by the Trump administration in 2018—continued, and the United States waived sanctions related to the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to appease European allies.In total, OFAC issued a total of 765 new designations and de-listed another 787 parties.By Treasury’s own estimate, there were roughly 9,421 sanctioned parties by late 2021—a 933 percent increase since 2000.

Source:U.S. Dep’t of Treasury, The Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review (Oct. 18, 2021)

OFAC sanctions developments tell only part of the story, as the United States continued to rely on export controls, foreign direct investment reviews, import restrictions, and restrictions with respect to the information and communications technology and services supply chain to accomplish foreign policy goals—often with a renewed emphasis on multilateral action.As in prior years, confronting the national security concerns associated with China remained a central focus of developments in U.S. export controls, especially those administered by the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”).In addition to confronting national security challenges, BIS took substantial steps to update the Export Administration Regulations, including addressing concerns associated with emerging and foundational technologies.As of this writing, the United States and its European allies were hammering out the details of an aggressive package of sanctions and export controls targeting Russia should the Kremlin follow through on threats to further invade Ukraine—presenting a key test of the Atlantic alliance and the ability of multilateral trade controls to deter a threatened use of force.

Contents

I. U.S. Trade Restrictions on China

A. Protecting Communications Networks and Sensitive Personal DataB. Slowing the Advance of China’s Military CapabilitiesC. Promoting Human Rights in XinjiangD. Promoting Human Rights in Hong KongE. Trade Imbalances and Tariffs

II. U.S. Sanctions

A. Treasury Department Sanctions ReviewB. MyanmarC. RussiaD. BelarusE. IranF. CubaG. EthiopiaH. Other Sanctions Developments

III. Information and Communications Technology and Services (ICTS)

A. Executive Order 13873: ICTS Supply Chain FrameworkB. Executive Order 14034: Connected Software ApplicationsC. Executive Order 14017: Supply Chain SecurityD. Executive Order 14028: CybersecurityE. Transatlantic Dialogues

IV. U.S. Export Controls

A. Commerce DepartmentB. Antiboycott DevelopmentsC. White House Export Controls and Human Rights InitiativeD. State Department

V. European Union

A. Sanctions DevelopmentsB. Export Controls DevelopmentsC. Noteworthy Judgments and Enforcement Actions

VI. United Kingdom

A. Sanctions DevelopmentsB. Export Controls DevelopmentsC. Noteworthy Judgments and Enforcement Actions

VII.People’s Republic of China

A. Countermeasures on Foreign SanctionsB. Export Controls RegimeC. Restrictions on Cross-Border Transfers of DataD. Security Review of Foreign Investments

______________________________

Despite the transition from the Trump to the Biden administration, U.S. trade policy toward China in 2021 was marked by a striking degree of continuity.As under the prior administration, the dozens of new China-related trade restrictions announced this year were generally calculated to advance a handful of longstanding U.S. policy interests for which there is broad bipartisan support within the United States, including protecting U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data; slowing the advance of China’s military capabilities; promoting human rights in Xinjiang and Hong Kong; and narrowing the bilateral trade deficit.As the Biden administration enters its second year in office and tensions between Washington and Beijing show few signs of abating, those core objectives of U.S. policy toward China appear unlikely to change, at least in the near term.

Meanwhile, as discussed more fully in Section VII, below, China this year deepened its already considerable efforts to resist U.S. pressure by adopting a host of new or expanded measures, including counter-sanctions, export controls, restrictions on cross-border data transfers, and a rigorous foreign investment review regime.In light of these new instruments in Beijing’s policy arsenal, multinational enterprises seeking to do business in both of the world’s largest economies now face the unenviable task of navigating between two competing, and often conflicting, sets of trade controls.

A.Protecting Communications Networks and Sensitive Personal Data

Spurred by concerns about Chinese espionage, the United States during 2021 sought to solidify trade restrictions designed to protect U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data.

Notably, President Biden on June 9, 2021 issued Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14034 to restrict the ability of “foreign adversaries,” including the People’s Republic of China, to access U.S. persons’ sensitive data.That measure revokes three Executive Orders that targeted by name certain Chinese connected software applications, including TikTok and various mobile payment platforms.In place of those restrictions, E.O. 14034 articulates a more neutral set of criteria that U.S. Executive branch agencies are to use in evaluating threats to sensitive data of U.S. persons.The Order also sets forth a more rigorous process, including the preparation of two reports by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, for recommending policy options to address the purported threat posed by such apps.From a policy perspective, these changes appear calculated to put the earlier, Trump-era restrictions on certain Chinese apps—which were effectively unenforceable, having been enjoined by multiple federal courts in September and October 2020—on firmer footing.

For a more detailed discussion of U.S. measures to secure information and communications technology and services against foreign interference, please see Section III, below.

B.Slowing the Advance of China’s Military Capabilities

Another key feature of the Biden administration’s trade policy in 2021 was its attempt to blunt the development of China’s military capabilities, including by restricting exports of U.S.-origin items to certain Chinese end-users, prohibiting U.S. persons from investing in the securities of dozens of “Chinese military-industrial complex companies,” and subjecting potential Chinese acquisitions of and investments in sensitive U.S. businesses to stringent foreign investment reviews.

Export controls this year remained a core element of U.S. efforts to slow Beijing’s emergence as a strategic competitor as the Biden administration frequently used Entity List designations to target PRC-based firms.In its expanding size, scope, and profile, the Entity List has begun to rival OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List as a tool of first resort when U.S. policymakers seek to wield coercive authority, especially against major economies and significant economic actors.Among the more than 80 Chinese firms added to the Entity List during 2021 were substantial enterprises such as China National Offshore Oil Corporation Ltd. and the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (“XPCC”).

Entities can be designated to the Entity List upon a determination by the End-User Review Committee (“ERC”)—which is composed of representatives of the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury—that the entities pose a significant risk of involvement in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.Through Entity List designations, BIS prohibits the export of specified U.S.-origin items to designated entities without BIS licensing.BIS will typically announce either a policy of denial or ad hoc evaluation of license requests.

The practical impact of any Entity List designation varies in part on the scope of items BIS defines as subject to the new export licensing requirement, which could include all or only some items that are subject to the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”).Those exporting to parties on the Entity List are also precluded from making use of any BIS license exceptions.However, because the Entity List prohibition applies only to exports of items that are “subject to the EAR,” even U.S. persons are still free to provide many kinds of services and to otherwise continue dealing with those designated in transactions that occur wholly outside of the United States and without items subject to the EAR.

The ERC has over the past several years steadily expanded the bases upon which companies and other organizations may be designated to the Entity List to include activities like enabling human rights violations and producing surveillance technology.During 2021, BIS continued this trend by announcing six rounds of Entity List designations tied to activities in support of China’s military.Among those designated in January, April, June, July, November, and December 2021 were more than 40 PRC entities for their alleged involvement in developing, for example, supercomputers, quantum computing technology, and biotechnology (including purported brain-control weaponry) for Chinese military applications.

As part of the growing use of export controls to slow the advance of China’s military capabilities, pursuant to the Military End Use / User Rule, exporters of certain listed items subject to the EAR require a license from BIS to provide such items to China, Russia, Venezuela, Burma, and Cambodia if the exporter knows or has reason to know that the exported items are intended for a “military end use” or “military end user.”In April 2020, BIS announced significant changes to these military end use and end user controls that became effective on June 29, 2020.In particular, where the prior formulation of the Military End Use / User Rule only captured items exported for the purpose of using, developing, or producing military items, the rule now covers items that merely “support or contribute to” those functions.The scope of “military end uses” subject to control was also expanded to include the operation, installation, maintenance, repair, overhaul, or refurbishing of military items.

The expanded Military End Use / User Rule has presented a host of compliance challenges for industry, prompting BIS in December 2020 to publish a new, non-exhaustive Military End User (“MEU”) List to help exporters determine which organizations are considered military end users.The 71 Chinese companies identified to date appear to be principally involved in the aerospace, aviation, and materials processing industries.Although no new Chinese entities have been added to the MEU List since state-owned Beijing Skyrizon Aviation Industry Investment Co., Ltd. was named in the final days of the Trump administration, the Biden administration has continued to administer and enforce the MEU List (as well as the underlying Military End Use / User Rule).As such, that policy tool remains readily available and could be used by BIS in coming months to target additional entities with alleged links to China’s security services.

In addition to expanding U.S. export controls targeting China, the Biden administration in June 2021 announced updated restrictions on the ability of U.S. persons to invest in publicly-traded securities of certain companies determined to operate in the defense and related materiel sector or the surveillance technology sector of China’s economy.

In place of earlier Trump-era restrictions, an Executive Order promulgated on June 3, 2021—which OFAC is calling E.O. 13959, as amended—prohibits U.S. persons from engaging in “the purchase or sale of any publicly traded securities, or any publicly traded securities that are derivative of such securities or are designed to provide investment exposure to such securities” of certain companies named by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.In particular, persons may now be designated a Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Company (“CMIC”) if they are determined by the Secretary of the Treasury:(1) to operate or have operated in the defense and related materiel sector or the surveillance technology sector of the economy of the People’s Republic of China, or (2) to own or control, or to be owned or controlled by, such a company.The designation criteria in E.O. 13959, as amended, are therefore broader than under the Trump-era restrictions in that they target surveillance technology companies.Indeed, the White House has indicated that it intends to use E.O. 13959, as amended, to target Chinese companies that “undermine the security or democratic values of the United States and our allies”—including especially by targeting Chinese surveillance technology companies whose activities enable surveillance beyond China’s borders, repression, and/or serious human rights abuses.

The investment restrictions set forth in E.O. 13959, as amended, take effect 60 days after a company becomes designated as a CMIC.U.S. persons have 365 days from a company’s designation date to divest their interest in that CMIC.Those investment restrictions presently target 68 companies that appear by name on a new Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (the “NS-CMIC List”) administered by OFAC.For the initial tranche of 59 companies that were added to the NS-CMIC List in June 2021, the investment restrictions came into effect on August 2, 2021, and U.S. persons have until June 3, 2022 to divest their interest in such firms.

From a policy perspective, the updated investment restrictions appear designed to provide greater clarity regarding precisely which PRC companies are being targeted.In that sense, E.O. 13959, as amended, seems to be a reaction to widespread market uncertainty concerning which entities were covered by the prior administration’s restrictions, along with a series of successful court challenges by companies like the smartphone maker Xiaomi that were previously named on the basis of a surprisingly thin evidentiary record.In our view, the updated restrictions appear calculated to put those earlier, Trump-era measures on firmer footing to withstand legal challenges—suggesting that the Biden administration is recalibrating investment restrictions targeting companies linked to China’s military-industrial complex to survive for the long term.

Although the Entity List, the MEU List, and the NS-CMIC List are analytically distinct from one another, all three measures appear to be driven by similar concerns among U.S. officials regarding the use of U.S. resources—namely, technology and capital—to engage in activities contrary to U.S. national security interests, including facilitating the expansion of China’s military capabilities.In addition to their shared policy underpinnings, the three lists are similar in that they are each tailored to restrict only certain narrow categories of transactions.Unlike a designation to OFAC’s SDN List—which generally results in U.S. persons being prohibited from engaging in substantially all transactions involving a targeted entity—the three lists discussed above are each less sweeping in their effects.The Entity List and the MEU List both impose a licensing requirement on exports, reexports, and transfers of certain U.S.-origin goods, software, and technology to named companies, many of which are located in China.The NS-CMIC List restricts U.S. persons from having investment exposure to publicly-traded securities of certain named Chinese companies.In each case, absent some other prohibition, U.S. and non-U.S. persons are permitted to continue engaging in all other lawful dealings with the listed entities.In that sense, these three lists each offer a potentially attractive option for U.S. officials looking to impose meaningful costs on large non-U.S. firms that act contrary to U.S. interests while avoiding the economic disruption of designating such enterprises to OFAC’s SDN List.

Consistent with a whole-of-government approach to limiting China’s access to sophisticated technologies with potential military applications, the United States during 2021 also leveraged the expanded authorities available to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS” or the “Committee”) to target sensitive investments by Chinese acquirers.Notably, a lengthy CFIUS investigation led the South Korea-based chipmaker Magnachip Semiconductor Corporation in December 2021 to abandon its planned acquisition by a PRC-based private equity firm, suggesting that the Committee is likely to remain intensely focused on blunting efforts by Chinese buyers to acquire advanced technologies in general and semiconductors in particular.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress has in parallel sought to bolster the United States’ ability to develop the technologies of the future.The U.S. Senate in June 2021 approved a sprawling bill authorizing approximately $250 billion in spending to better position the United States to compete technologically with China, including through investments in research and development and semiconductor manufacturing.The measure, called the United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 (“USICA”), passed the Senate by a wide bipartisan majority—suggesting that countering China’s growing influence remains one of the few areas of agreement between congressional Republicans and Democrats.Debate over the USICA will soon shift to a conference committee between the Senate and the House of Representatives, where the measure is expected to undergo further changes during coming months.Although it is uncertain whether and in what form the bill will ultimately be approved by both chambers of Congress, in light of the bill’s broad base of support—including from President Biden—some version of the USICA appears likely to be passed by Congress and signed into law later this year.

C.Promoting Human Rights in Xinjiang

During 2021, the United States continued to ramp up legislative and regulatory efforts to address and punish reported human rights abuses, including high-tech surveillance of Muslim minority groups and forced labor, in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (“Xinjiang”).

The Biden administration took a number of executive actions against Chinese individuals and entities implicated in the alleged Xinjiang repression campaign.In March and December 2021, OFAC—acting in concert with the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Canada— designated to the SDN List four current or former PRC government officials for their ties to mass detention programs and other abuses.In December 2021, OFAC followed up on those designations by adding to the NS-CMIC List a total of nine Chinese surveillance technology companies for their role in enabling surveillance beyond China’s borders, repression, and/or serious human rights abuses.Specifically, OFAC on December 10, 2021 named China-based SenseTime Group Limited a CMIC for owning a company alleged to have developed facial recognition programs “that can determine a target’s ethnicity, with a particular focus on identifying ethnic Uyghurs.”The following week, OFAC on December 16, 2021 named a further eight Chinese technology companies to the NS-CMIC List for operating in the surveillance technology sector of China’s economy and/or for owning or controlling such an entity.Those eight firms were similarly targeted for their alleged involvement in developing technologies that have been used to—and, some cases, were specifically designed to—track members of ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang, including especially ethnic Uyghurs.In addition to enabling the biometric tracking and surveillance of minorities in China, a further risk factor for designation to the NS-CMIC List appears to be the export of such surveillance technologies to regimes with troubling human rights records, for which several of the entities identified by OFAC were cited.

In tandem with sanctions designations, the United States during 2021 leveraged export controls to advance the U.S. policy interest in curtailing human rights abuses in Xinjiang—most notably through expanded use of the Entity List.Continuing a trend begun in October 2019, the ERC on two separate occasions this past year—in June and July 2021—added a total of 19 Chinese organizations to the Entity List for their involvement in human rights violations against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang.Entities so designated included the silicon producer Hoshine Silicon Industry (Shanshan) Co., Ltd. (“Hoshine”) and the Chinese state-owned paramilitary organization XPCC, each for participating in the practice of, accepting, or utilizing forced labor in Xinjiang.

Consistent with the Biden administration’s whole-of-government approach to trade with China, the United States also used import restrictions—including multiple withhold release orders issued by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”) and enactment of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act—to deny certain goods produced in Xinjiang access to the U.S. market.

CBP is authorized to enforce Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930, which prohibits the importation of foreign goods produced with forced or child labor.Upon determining that there is information that reasonably, but not conclusively, indicates that goods that are being, or are likely to be, imported into the United States may be produced with forced or child labor, CBP may issue a withhold release order, or WRO, which requires the detention of such goods at any U.S. port.To overcome a WRO and have its goods released into the United States, the importer bears the burden of demonstrating by evidence satisfactory to the Commissioner of CBP that the goods were not made, in whole or in part, with a prohibited form of labor—which, as a practical matter, is a difficult showing to make.

After issuing a record number of withhold release orders during 2020, CBP in January 2021 continued its aggressive use of this policy instrument by imposing a region-wide WRO targeting all cotton products and tomato products produced in whole or in part in Xinjiang.In June 2021, CBP issued a company-specific WRO targeting silica-based products—which are commonly used in solar panels and electronics—made by the Xinjiang-based company Hoshine and its subsidiaries.Underscoring the degree to which U.S. trade controls targeting China overlap and intersect, Hoshine was concurrently added to the Commerce Department’s Entity List, thereby constraining the company’s ability to both source inputs from, and sell goods into, the U.S. market.

Concerns regarding the PRC’s activities in Xinjiang appear to be shared by bipartisan majorities within the U.S. Congress.In December 2021, Congress passed and President Biden signed into law the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (the “Uyghur Act”), which in effect subjects all goods sourced from Xinjiang to a withhold release order.A key feature of that legislation is the creation of a rebuttable presumption—which takes effect on June 21, 2022—that all goods mined, produced, or manufactured even partially within Xinjiang are the product of forced labor and are therefore not entitled to entry at U.S. ports.Although the presumption can be overcome by “clear and convincing” evidence, the nature of which is to be articulated in formal guidance later this year, importers may face substantial practical hurdles to conducting due diligence into their supply chains as PRC entities have historically been unwilling to submit to audits of their labor practices.(Moreover, PRC entities may be prohibited by local law from cooperating with such requests in light of China’s new counter-sanctions measures, discussed in Section VII, below.)In addition to imposing import restrictions, the new law also amends the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020 to authorize the President to impose sanctions on persons determined to be responsible for serious human rights abuses in connection with forced labor.For a more detailed description of the Uyghur Act and its implications for companies doing business in or related to Xinjiang, please see our January 2022 client alert.

As a complement to the legislative and regulatory changes described above, the Biden administration published guidance to assist the business community in conducting human rights due diligence related to Xinjiang.On July 13, 2021, the U.S. Departments of State, Treasury, Commerce, Homeland Security, and Labor, together with the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, issued an updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory.That document spotlights practices by PRC authorities that the U.S. Government considers objectionable, including especially related to forced labor and mass surveillance.The Advisory identifies “red flags” that individuals or entities linked to Xinjiang may be using forced labor, including dealing in certain types of goods (such as cotton and polysilicon) or operating facilities located within or near known internment camps and prisons.

D.Promoting Human Rights in Hong Kong

As Beijing continued to tighten its grip on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the territory remained an area of focus for U.S. sanctions policy under the Biden administration.Building on policy measures announced during the preceding year—including revocation of Hong Kong’s special trading status under U.S. law, passage of the Hong Kong Autonomy Act, and the imposition of blocking sanctions against the territory’s chief executive, Carrie Lam—2021 witnessed multiple rounds of Hong Kong-related sanctions designations.Among those added to the SDN List for their alleged involvement in eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy were numerous current PRC government officials.

Additionally, the Biden administration on July 16, 2021 published a new Hong Kong Business Advisory that describes the potential financial, legal and reputational risks that can arise from operating in Hong Kong.The Advisory, which was timed to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the Hong Kong national security law, spotlights in particular the possibility of arrest under the national security law, warrantless electronic surveillance, and restrictions on the free flow of information.The Advisory also provides a helpful compilation of the U.S. legal authorities pursuant to which Hong Kong and mainland Chinese individuals and entities may be sanctioned and warns that U.S. businesses may suffer consequences for complying with those measures under China’s new counter-sanctions law, which we discuss in more detail in Section VII.A, below.

E.Trade Imbalances and Tariffs

Also in 2021, the Biden administration continued to make broad use of its authority to impose tariffs on Chinese-made goods.This policy approach—which was launched during the Trump era—remains the subject of substantial and ongoing litigation at the U.S. Court of International Trade.Among the mechanisms that the new administration has employed to retain significant tariffs targeting Beijing is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (“Section 301”), which allows the President to direct the U.S. Trade Representative to take all “appropriate and feasible action within the power of the President” to eliminate unfair trade practices or policies by a foreign country.

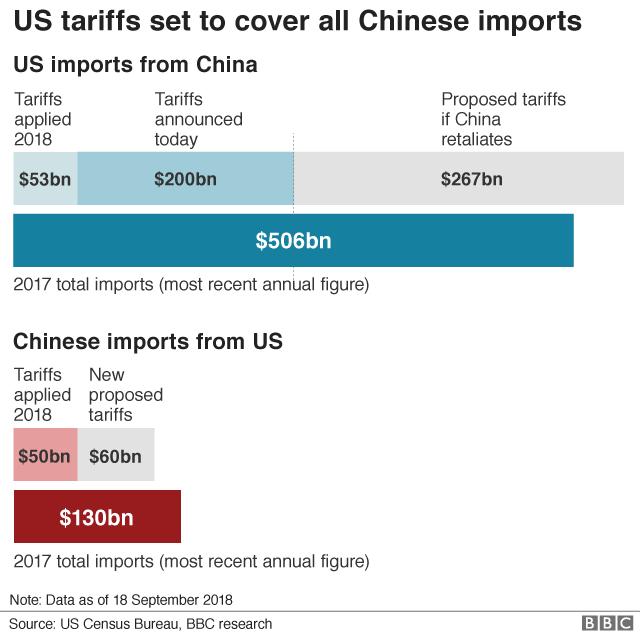

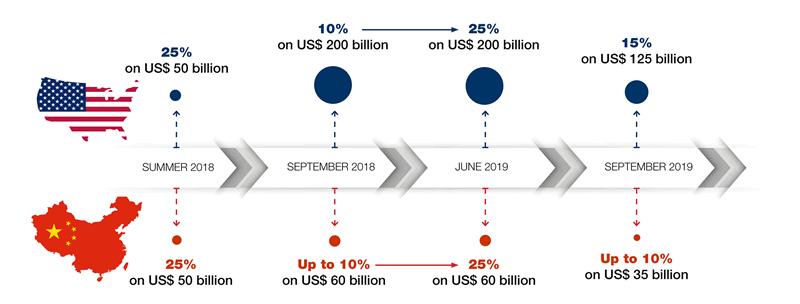

Although the Trump administration initiated Section 301 tariff investigations involving multiple jurisdictions, the Section 301 tariffs that have dominated the headlines are the tariffs imposed on China in retaliation for practices with respect to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation that the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative has determined to be unfair (“China 301 Tariffs”).The China 301 Tariffs were imposed in a series of waves in 2018 and 2019, and as originally implemented they together cover over $500 billion in products from China.

As we predicted in our 2020 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, although the China 301 Tariffs were a hallmark of the Trump administration’s trade policy, they have so far remained in place under President Biden and the new administration appears disinclined to relax those measures without first extracting concessions from Beijing.

A.Treasury Department Sanctions Review

In early 2021, the incoming Biden administration signaled its intent to evaluate the way the United States utilizes sanctions as a tool of foreign policy—often putting aside questions regarding the fate of a long list of Trump-era policies while the review was ongoing.The Treasury Department released the findings from its sanctions review in October 2021.In that document, Treasury articulates both the emerging challenges to the efficacy of sanctions as a national security tool, as well as a set of principles to guide U.S. sanctions policymaking in the future.

As part of a broader effort to ensure that sanctions—the use of which has sharply expanded during the past two decades—remain a durable and effective policy instrument, Treasury in its review emphasized that U.S. sanctions policies should be tied to clear, discrete objectives that are consistent with relevant Presidential guidance.To accomplish that goal, Treasury indicated that it would on a going-forward basis adopt the use of a structured policy framework—similar to the rigorous process that informs the use of force by the U.S. military—by asking whether a proposed sanctions action:

These principles were broadly apparent in the sanctions policy decisions made by the U.S. administration throughout 2021 as OFAC often announced new sanctions actions in coordination with close U.S. allies and issued numerous humanitarian general licenses to minimize the collateral consequences of U.S. measures on vulnerable populations such as the people of Afghanistan.

B.Myanmar

As we wrote in February and April 2021, the Biden administration imposed new sanctions on Myanmar (also called “Burma”) in response to the Myanmar military’s coup against the country’s elected civilian government on February 1, 2021.Since then, the military (called the “Tatmadaw”) has maintained tight control over the country by, among other things, using lethal force on protesters, issuing a series of martial law orders, and imprisoning civilian leaders like State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi.As the situation worsened, the Biden administration continued to enhance sanctions, notably opting for a targeted, list-based approach instead of jurisdiction-wide measures like those on Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and the Crimea region of Ukraine.

The turmoil in Myanmar marks an unfortunate echo of the past.Suu Kyi had been detained by the military in the 1990s and early 2000s and the international community, led by the United States, had previously responded with sanctions.Myanmar eventually moved toward democratization, with one key pivot point being the overwhelming victory of Suu Kyi’s political party, the National League for Democracy, in the country’s November 2015 elections.As we noted back in May 2016, the U.S. Government responded by easing sanctions pressure on Myanmar, eventually dismantling the country-specific sanctions program administered by OFAC.While there was no longer a Myanmar sanctions program, in the ensuing years OFAC continued to sanction Myanmar-based actors under other programs targeting specific behaviors such as narcotics trafficking, weapons proliferation, and human rights abuses—with an emphasis on the military-linked perpetrators of violence against the Rohingya, a religious minority group, in 2016 and 2017.

In the wake of the February 2021 military coup, rather than revive the former Myanmar sanctions program, President Biden created a new one by issuing Executive Order 14014.Under this authority, OFAC may designate to the SDN List individuals and entities determined to be directly or indirectly causing, maintaining, or exacerbating the situation in Myanmar, and/or leading Myanmar’s military or current government, or operating in the country’s defense sector.Under E.O. 14014, OFAC may also designate the adult relatives of a designee, the entities owned or controlled by a designee, or those providing material support to a designee.

The breadth of the designation criteria in E.O. 14014 affords the administration considerable flexibility in selecting its targets.The Biden administration has taken full advantage.During the past year, OFAC has sanctioned, among others, leaders of the Tatmadaw and their relatives, military-run governmental entities and their leaders, and military-linked businesses operating across economic sectors.

The March 2021 designation of two military conglomerates—Myanmar Economic Holdings Public Company Limited (“MEHL”) and Myanmar Economic Corporation Limited (“MEC”)—is arguably the most consequential of the designations thus far.As we discussed in April 2021, by operation of OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule, the sanctioned status of MEHL and MEC automatically flows down to their dozens of majority-owned subsidiaries that play foundational roles throughout the country’s economy, implicating the Myanmar-based operations of numerous foreign companies with touchpoints with the United States.Recognizing the potential collateral impact of targeting such key economic actors, OFAC issued a set of four general licenses authorizing the wind down of transactions involving MEHL or MEC for a set time period (which has since lapsed), and authorizing activities conducted by the U.S. Government and certain international organizations and non-profits.

It is also worth noting that OFAC in May 2021 designated the State Administrative Council (the “SAC”), the governmental body established by the Tatmadaw to govern Myanmar.The consequences of the SAC’s designation have been challenging to discern for companies doing business in Myanmar that deal directly or indirectly with the government.In our view, some clarity can be gained by looking to OFAC’s historical practices.When OFAC imposed sanctions on the Government of Venezuela, for example, it was explicit in the underlying authority, Executive Order 13884, that the entire Maduro regime was being targeted.The agency also promulgated numerous Venezuela-related general licenses to protect innocent third parties from what was a massively impactful measure.In contrast, the SAC designation, on its face, singled out one governmental entity, with no corresponding general licenses issued.The intended effect here appears to us to have been targeted, as opposed to sweeping, restrictions.

Over the past year or so, OFAC has designated 87 individuals and entities pursuant to E.O. 14014—not all at once but in recurring waves of designations, often prompted by particular atrocities committed by the Tatmadaw.President Biden has to date taken a calibrated and incremental approach to exerting economic pressure on Myanmar, but the tools used have been wide-ranging—extending beyond sanctions to include export controls, import controls, anti-money-laundering, and labor measures.Indeed, on January 26, 2022, the U.S. Departments of Treasury, State, Commerce, Labor, and Homeland Security, plus the Executive Office of the President, jointly published a Burma Business Advisory summarizing these measures and highlighting sectors, activities, and actors that the U.S. Government considers high risk.Absent dramatic developments on the ground, we would expect this gradual and whole-of-government approach to continue so long as the Tatmadaw remains in power in Myanmar.If the Biden administration decides to further increase pressure, the expected departure of major Western energy firms with a longtime presence in the country could soon open the way to sanctions on state-owned Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, or MOGE, which is a key source of revenue for the military regime in Yangon.

C.Russia

Russia featured prominently in President Biden’s first year of foreign policy developments and challenges, as demonstrated by a range of sanctions actions aimed at the Kremlin.These actions—largely geared toward addressing Russia’s meddling abroad, including the annexation of Crimea, foreign election interference, and the SolarWinds cyberattack—have been relatively measured to date, reflecting concerns about potential impacts on European allies.However, an open question as of this writing is whether the Russian military buildup along the Ukrainian border will escalate into a further incursion into Ukrainian territory, which could trigger the imposition of biting sanctions and export controls by the United States and its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (“NATO”) allies.

In May 2021, the Biden administration waived sanctions on Nord Stream 2 AG, the Russian-controlled company developing the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, along with the company’s chief executive.A State Department press release noted that the agency determined that, with respect to those two parties, “it is in the national interest of the United States to waive” sanctions authorized by the Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act of 2019.The waiver came at the behest of Germany, with which the Biden administration has sought to strengthen ties.However, the action drew sharp criticism within the United States, including from both sides of the aisle in the U.S. Congress.Opponents of the project contend that, once complete, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline could strengthen Russia’s hand by positioning the Kremlin to withhold gas supplies from European consumers and deprive Ukraine of gas transit fees, a key source of government revenue.The waiver subsequently gave rise to a blockade by Senate Republicans of dozens of Biden administration national security-related nominations, as well as vigorous debate in the halls of Congress concerning the amount of discretion that should be afforded to the Executive branch in determining whether to impose further sanctions on Russia.

In two separate actions taken in March and August 2021, the United States imposed sanctions on Russia in response to the 2020 poisoning of the Russian dissident and activist Aleksey Navalny.The measures, which were implemented pursuant to the Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991 and various other U.S. legal authorities, expanded on sanctions imposed three years earlier in connection with a similar chemical attack on Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom.

The March 2021 action consisted of the designation to the SDN List of seven Russian government officials involved in the attack and Navalny’s subsequent arrest and imprisonment.At the same time, the Department of Commerce added 14 entities to the Entity List based on their support to Russia’s chemical and weapons of mass destruction industries, and the Department of State expanded existing sanctions against multiple individuals and entities in Russian’s chemical weapons sector.In connection with this action, the U.S. Government is also now prohibited from providing foreign assistance or authorizing arms sales, arms sales financing, U.S. Government credit, and exports of national security-sensitive goods and technology to Russia.EAR license exceptions GOV, ENC, BAG, TMP, and AVS remain available, and the U.S. Government will consider licenses necessary for flight safety, certain deemed exports, exports to wholly owned subsidiaries of U.S. and foreign companies in Russia, and exports in support of government space cooperation on a case-by-case basis.Commercial end users, state-owned enterprises, and exports in support of commercial space launches are subject to a presumption of denial.

In August 2021, the State Department, acting pursuant to Executive Order 14024 (described below), imposed restrictions on two Russian Ministry of Defense scientific institutes and OFAC designated to the SDN List additional individuals associated with Russia’s foreign intelligence agency, the Federal Security Service (commonly referred to by its Russian acronym, the FSB), for their role in the Navalny poisoning.

As described in more detail in an earlier client alert, the United States on April 15, 2021 announced a significant expansion of sanctions on Russia for a range of harmful foreign activities such as the annexation of Crimea and interference with U.S. elections.The sanctions included new restrictions on the ability of U.S. financial institutions to deal in Russian sovereign debt and the designation of more than 40 individuals and entities for supporting the Kremlin’s malign activities abroad.The basis for these actions, Executive Order 14024, relied in large part on earlier Executive Orders and actions, but also expanded Treasury’s authorities to, for example, designate the spouse and adult children of sanctioned individuals, which could enable the future targeting of members of the Russian oligarchy and their close relatives.Other provisions in these and related actions taken by the Treasury Department suggest the Biden administration stopped short of adopting more draconian measures such as blacklisting either Russia’s sovereign wealth fund or the Russian government itself.Those policy options therefore remain available in the event of a further significant deterioration in relations between Washington and Moscow.

Meanwhile, as tens of thousands of Russian troops continue in early 2022 to mass on the border with Ukraine, the United States and its NATO allies have threatened a barrage of sanctions and export controls should Russia mount a further invasion of its western neighbor.As diplomatic talks regarding the security of Eastern Europe unfold, the White House has suggested that the United States and its allies could respond to Russian military aggression in Ukraine by barring Russian access to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (“SWIFT”) messaging system that underlies global financial transactions.Additional possible consequences such as sanctions on major Russian banks and stringent controls on exports to Russia of semiconductors and electronics—all of which the White House has suggested could be imposed within hours of a Russian incursion—could severely disrupt the global economy in the near term.

D.Belarus

In keeping with one of the key recommendations of the Treasury Department’s sanctions review, discussed above, the United States, in close collaboration with the European Union, United Kingdom, and Canada, imposed coordinated sanctions against individuals and entities associated with the deterioration in democratic norms and human rights in Belarus.OFAC emphasized that this effort “reflects the United States’ commitment to acting with its allies and partners to demonstrate a broad unity of purpose” because “sanctions are most effective when coordinated where possible with allies and partners who can magnify the economic and political impact.”

On April 19, 2021, subject to a wind-down period that has since expired, OFAC revoked a longstanding general license that authorized U.S. persons to engage in certain transactions involving nine sanctioned Belarusian state-owned enterprises.As described by the U.S. Department of State, that authorization was withdrawn in light of the human rights record of Belarusian leader Aleksandr Lukashenka and his regime, including the ongoing detention of hundreds of political prisoners following the country’s August 2020 presidential election.

Following the May 2021 forced diversion of a commercial airliner by the Lukashenka regime and the subsequent arrest of dissent journalist Raman Pratasevich—described by some observers as a state-sponsored hijacking—OFAC on June 21, 2021 designated an additional 16 individuals and five entities.Among those added to the SDN List were senior Belarusian government officials and government agencies, including the State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus (the “Belarusian KGB”) and its chairman.OFAC concurrently issued a general license authorizing U.S. persons to engage in certain transactions involving the Belarusian KGB in its administrative capacity such as complying with law enforcement actions and investigations.

To mark the one-year anniversary of Belarus’ fraudulent presidential election, President Biden on August 9, 2021 signed Executive Order 14038 authorizing sanctions on Belarusian government agencies and officials, as well as individuals and entities determined to operate or have operated in certain identified sectors of the Belarusian economy.Targeted industries include the defense and related material, security, energy, potassium chloride (potash), tobacco products, construction, and transportation sectors, plus any other sector of the Belarusian economy that may subsequently be determined by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.In parallel, OFAC designated a further 23 individuals and 21 entities, including numerous parties identified as “wallets” for Lukashenka and his regime.

In late 2021, relations between Minsk and the West continued to spiral downward as the Lukashenka regime encouraged waves of vulnerable migrants to transit Belarusian territory and cross into the European Union.Following this development, OFAC on December 2, 2021 added Belarus to the short list of countries (including Russia and Venezuela) that are subject to sectoral sanctions.In particular, OFAC issued Directive 1 Under Executive Order 14038 prohibiting U.S. persons from transacting in, providing financing for, or participating in other dealings in the primary and secondary markets for “new” debt with a maturity of greater than 90 days issued by the Ministry of Finance or the Development Bank of the Republic of Belarus.OFAC indicated in published guidance that these sectoral restrictions apply only to the two named entities (and not their subsidiaries), and that absent some other prohibition, U.S. persons may continue engaging in all other lawful dealings with those two entities.OFAC concurrently designated a further 20 individuals and 12 entities, and identified three aircraft as blocked property.These designations targeted parties that financially prop up the regime, and those implicated in the Lukashenka regime’s smuggling of migrants into the European Union.

E.Iran

The advent of the Biden administration brought to the foreground the question of the future of the JCPOA.In 2021, events unfolded much as we anticipated in our 2020 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update.Consistent with the interest that both President Biden and then-Iranian President Hassan Rouhani had signaled in returning to the JCPOA, negotiations resumed in April 2021 against a tense backdrop as Iran announced plans to begin enriching uranium to 60 percent purity.Tehran’s unveiling of new centrifuges was soon followed by an explosion at the Natanz nuclear enrichment facility that has been widely attributed to Israeli sabotage.

Although talks initially appeared to progress, negotiations stalled following the June 2021 election of current Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi—a hardliner who was previously (and remains) designated to the SDN List.Raisi was initially targeted in 2019 for his role as head of the Iranian judiciary in overseeing human rights abuses and, in an earlier role as prosecutor general, participating in a “death commission” that ordered the extrajudicial killing of thousands of political prisoners.Since assuming the presidency, Raisi has expressed support for a return to the JCPOA, and indirect talks resumed at the end of November 2021.

Progress in the resumed negotiations remains limited, and Iran meanwhile continues to advance its nuclear program—a trend that U.S. and European officials have indicated is not sustainable.On January 20, 2022, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that it is “really now a matter of weeks” to “determine whether or not we can return to mutual compliance with the agreement,” a sentiment echoed by his French and German counterparts.

In the absence of a return to or renegotiation of the nuclear deal, the architecture of the Iran sanctions program has thus far not substantially changed since President Biden took office.However, OFAC continued to make use of its existing counter-terrorism authority to issue a significant set of designations in September 2021 targeting Hizballah and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force.Both organizations had already been designated to the SDN List pursuant to OFAC’s counter-terrorism authority.The new designations target individuals and companies providing financial support to them, including the operation of a network for smuggling and selling valuable commodities, including gold, electronics, and currency, and laundering the proceeds through the international financial system.This action suggests that, with or without progress in the JCPOA talks, OFAC is likely to continue using its existing authorities to target Iran’s perceived malign activities.

F.Cuba

First established six decades ago following Cuba’s Communist Revolution, U.S. sanctions on the regime in Havana have lately oscillated between easing under President Obama and tightening under President Trump.Despite early speculation that the Biden administration might seek a renewed thaw in relations with Havana, prospects for relaxed U.S. sanctions were dashed as the Cuban government in July 2021 cracked down on a wave of peaceful protects by Cuban citizens.

The Biden administration in July and August 2021 soon announced four rounds of sanctions against Cuban government entities and senior officials, including the country’s defense minister, pursuant to OFAC’s Global Magnitsky sanctions authority which targets perpetrators of serious human rights abuse and corruption.On August 11, 2021, OFAC and BIS jointly issued a fact sheet highlighting the U.S. Government’s longstanding policy commitment to ensuring the free flow of information to the Cuban people.In the wake of these developments, U.S. sanctions on Cuba—including the country’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism by the outgoing Trump administration—have remained substantially unaltered over the past year and show few signs of changing in the near term as the United States enters a pivotal election year.

G.Ethiopia

On September 17, 2021, OFAC launched a new Ethiopia-related sanctions program in response to the ongoing humanitarian and human rights crisis in Ethiopia, particularly in the country’s Tigray region.This program, which we discuss in depth in a recent client alert, authorizes OFAC to impose sanctions measures of varying degrees of severity without those sanctions necessarily flowing down to entities owned by sanctioned parties, suggesting that the United States is aiming to limit ripple effects on the Ethiopian economy.

Executive Order 14046 permits the Department of the Treasury to choose from a menu of blocking and non-blocking sanctions measures, allowing for a targeted application of restrictions.In keeping with recent Executive Orders of its kind, the criteria for designation under the E.O. are exceedingly broad.The Secretary of the Treasury can designate foreign persons for a wide range of activities related to the crisis in northern Ethiopia.These criteria range from obstructing access to humanitarian assistance and targeting civilians through acts of violence to being a political subdivision, agency, or instrumentality of the Ethiopian or Eritrean governments or of certain political parties.Upon designation of any such foreign person, the Secretary of Treasury may select from a menu of sanctions, including both blocking and non-blocking measures such as prohibiting U.S. persons from engaging in certain transactions with sanctioned persons involving significant amounts of equity or debt instruments, loans, credit, or foreign exchange.

Notably, unlike nearly all other sanctions programs administered by OFAC, E.O. 14046 stipulates that OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule does not automatically apply to any entity “owned in whole or in part, directly or indirectly, by one or more sanctioned persons, unless the entity is itself a sanctioned person” and the sanctions outlined within the E.O. are specifically applied.OFAC has indicated in published guidance that E.O. 14046’s restrictions do not automatically “flow down” to entities owned in whole or in part by sanctioned persons unless such persons appear by name on either OFAC’s SDN List or the agency’s Non-SDN Menu-Based Sanctions (“NS-MBS”) List.

Concurrent with the announcement of its Ethiopia-related sanctions, OFAC issued three general licenses in recognition of the importance of ongoing humanitarian efforts to address the crisis in northern Ethiopia.These general licenses authorize a wide range of transactions and activities carried out by enumerated international organizations and non-governmental organizations to address this humanitarian and human rights crisis, as well as humanitarian trade in agricultural commodities, medicine, and medical devices.

Nearly two months after the program was created, OFAC announced its first (and so far only) round of Ethiopia-related designations on November 12, 2021, issuing blocking sanctions against four entities and two individuals.Among those targeted were the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, Eritrea’s sole legal political party, and the Eritrean Defense Force (“EDF”), Eritrea’s military.OFAC in making that announcement highlighted reports of EDF looting, sexual assault, killing of civilians, and blocking of humanitarian aid.

H.Other Sanctions Developments

OFAC this year intensified its focus on digital currencies and ransomware by issuing multiple rounds of industry guidance and announcing the first U.S. sanctions designation of a virtual currency exchange.As cybercrime and ransomware schemes proliferate, OFAC appears poised to continue pursuing investigations and enforcement actions in the virtual currency space.

The total dollar value of ransomware-related reports filed with the U.S. Department of the Treasury more than doubled in 2021 compared against the prior year, according to information published by Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”).As reported by FinCEN, financial institutions filed over 600 ransomware-related suspicious activity reports during the first half of 2021, and the average payment amount for ransomware-related transactions was over $100,000.Of course, the May 7, 2021, ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline, the largest pipeline system for refined oil products in the United States, involved a much larger sum—nearly $5 million, paid via Bitcoin—and focused global attention on the connection between cybercrime and digital currencies.

At the end of 2020 and in early 2021, OFAC published two enforcement actions against virtual currency services providers, BitPay and BitGo.BitPay, headquartered in Atlanta, provides a payment processing solution for merchants to accept digital currency as payment for goods and services.While BitPay screened its direct customers, the merchants, against OFAC restricted party lists, the company failed to use information it received about the merchants’ customers at the time of a transaction, including a buyer’s name, address, email address, phone number, and Internet Protocol (“IP”) address, to determine whether buyers were located in sanctioned jurisdictions.BitGo, headquartered in California, failed to use IP address information it obtained regarding its direct customers for security purposes to also determine whether its customers were located in comprehensively sanctioned jurisdictions.

Both enforcement actions demonstrate OFAC’s expectation that best practices with respect to sanctions compliance, including IP address geo-blocking and sanctions list screening, apply to virtual currency services providers to the same extent as traditional financial institutions.Additional details on those two enforcement actions can be found in our February 2021 client alert.

On September 21, 2021, OFAC took more severe action against SUEX OTC (“SUEX”), a virtual currency exchange headquartered in Moscow, by adding SUEX to the SDN List, essentially barring SUEX from transactions that utilize the U.S. financial system and prohibiting U.S. persons from engaging in transactions involving the company.According to OFAC, SUEX facilitated transactions involving illicit proceeds from at least eight ransomware variants and over 40 percent of SUEX’s known transaction history is associated with illicit actors.That action—which marked the first time that OFAC has designated a virtual currency exchange to the SDN List—was soon followed by the SDN designation of the Chatex virtual currency exchange in November 2021.

Underscoring the agency’s heightened focus on this space, in addition to pursuing enforcement actions and blacklisting alleged bad actors, OFAC in September 2021 published an updated Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments.That document emphasizes that ransomware payments carry an elevated risk of dealing with prohibited parties.Expanding on earlier guidance, the Advisory also notes that, should an apparent sanctions violation occur in connection with a ransomware payment, OFAC will now take into account both the subject person’s cybersecurity practices and whether the ransomware attack was timely self-reported to U.S. authorities in determining what enforcement response to impose.OFAC in October 2021 also published an industry-specific handbook, titled Sanctions Compliance Guidance for the Virtual Currency Industry, that provides a comprehensive overview of OFAC’s sanctions programs, requirements, and resources for establishing a sanctions compliance program.Among other measures, OFAC suggests that virtual currency industry participants, consistent with a risk-based approach to sanctions compliance, consider implementing IP address geo-blocking, restricted party screening, and periodic “lookback” reviews after the agency adds new virtual currency addresses to the SDN List.

A major reversal of Trump-era sanctions policy occurred on April 5, 2021 when the Biden administration announced the revocation of Executive Order 13928, which had authorized sanctions against foreign persons determined to have engaged in any effort by the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) to investigate, arrest, detain, or prosecute United States or any U.S. ally personnel without the consent of the United States or that ally.As previously mentioned in our 2020 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, that earlier Executive Order came in retaliation for the ICC’s 2020 announcement of a human rights investigation into potential war crimes committed by U.S. troops, the Taliban, and Afghan forces in Afghanistan.As part of the Biden administration’s revocation, OFAC announced the elimination of the International Criminal Court-Related Sanctions Regulations and the removal from the SDN List of ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and Phakiso Mochochoko, the Head of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity, and Cooperation Division of the Office of the Prosecutor.

The reasoning for this reversal, according to the State Department, was that although the U.S. “maintain[s] our longstanding objection to the Court’s efforts to assert jurisdiction over personnel of non-States Parties such as the United States and Israel,” the new administration felt that those concerns “would be better addressed through engagement with all stakeholders in the ICC process rather than through the imposition of sanctions.”Given that the ICC sanctions were enacted without coordination with or support from traditional U.S. allies, this action appears to have been part of the Biden administration’s broader push to normalize and improve strained relationships between the United States and its foreign partners.

In the wake of the Taliban’s de facto takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, two longstanding sets of U.S. sanctions substantially complicated efforts by outside aid organizations to deliver humanitarian relief to the Afghan people.

Although Afghanistan itself is not subject to comprehensive U.S. sanctions, the Taliban have since 2001 been designated pursuant to E.O. 13224, which is administered through the Global Terrorism Sanctions Regulations and targets named foreign individuals, groups, and entities “associated with” designated terrorists.U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the targeted individuals and entities—referred to as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (“SDGTs”)—and all property and interests in property of an SDGT that come within U.S. jurisdiction are frozen.

The Taliban’s designation as an SDGT presents serious practical challenges now that, as of August 2021, the organization exercises de facto control over the Afghan state.By operation of OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule, the prohibitions on dealing with an SDGT (or other type of blocked person) extend to entities owned fifty percent or more in the aggregate by one or more SDGTs (or other type of blocked persons).That longstanding OFAC policy raises substantial questions as to whether the Taliban’s status as an SDGT applies by operation of law to dealings involving the Government of Afghanistan or perhaps more broadly the entire jurisdiction of Afghanistan.OFAC between September and December 2021 issued six general licenses authorizing U.S. persons to engage in various transactions to facilitate the provision of humanitarian aid to the people of Afghanistan; however, there is increasing concern that such humanitarian-focused authorizations may not be sufficient to protect the country’s fragile economy and the livelihoods of ordinary Afghans.While the accompanying guidance states that “[t]here are no OFAC-administered sanctions that generally prohibit the export or reexport of goods or services to Afghanistan, moving or sending money into and out of Afghanistan, or activities in Afghanistan,” the agency remains firm that such transactions cannot “involve sanctioned individuals, entities, or property in which sanctioned individuals and entities have an interest,” thereby leaving much of this ambiguity unanswered.The paucity of guidance on this point is further complicated by the lack of precedent for the circumstance in Afghanistan in which a sanctioned terrorist entity has seized control of an entire state, thereby offering the private sector few other points of reference.

In addition to U.S. sanctions targeting SDGTs, Section 302 of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (“AEDPA”) authorizes the U.S. Secretary of State to designate an organization as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (“FTO”) based on its status as a non-U.S. organization engaged in “terrorist activity” that poses a threat to U.S. nationals or national security.Under AEDPA, the Secretary of State may designate FTOs after consultation with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Attorney General.AEDPA also authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to require financial institutions to block funds in their possession or control in which a designated FTO maintains an interest.Section 303 of the Act makes it a crime for persons within the United States or under U.S. jurisdiction to knowingly provide material support to an FTO, which term encompasses nearly all forms of property, as well as the provision of services such as transportation.OFAC implements Section 302 of AEDPA through the Foreign Terrorist Organizations Sanctions Regulations.Presently, 75 organizations are designated FTOs.Although the Taliban is not itself an FTO as of this writing, various organizations closely affiliated with the Taliban, including the Haqqani Network, members of which now occupy key Afghan government posts, are subject to such restrictions.

Uncertainty regarding the applicability of these two sets of sanctions restrictions, together with de-risking by multinational financial institutions, appears to have exacerbated one of the worst humanitarian crises in modern history, with more than 20 million Afghans reportedly on the brink of famine.Afghan banks have closed and, while some financial services have resumed in key cities, currency is in short supply and the movement of funds even internally within Afghanistan is challenging.The Afghan government has scant official assets located domestically and, given the Taliban sanctions, the country has been shut off from its modest assets domiciled abroad.

Notably, OFAC has maintained a freeze on the approximately $9.4 billion of Afghanistan’s foreign reserves located at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and to date has only issued general licenses that apply to the provision of medical and humanitarian aid to non-governmental instrumentalities.A significant degree of uncertainty remains for the private sector regarding to what extent it would be permitted to engage with anyone within Afghanistan, if at all, beyond the confines of applicable licenses.

Although OFAC continued to designate new sanctions targets at a steady clip, there were also a number of significant removals from the SDN List during 2021, highlighting that OFAC views sanctions as reversible and designed to change behavior.One of the most consequential recent de-listings took place in December 2021 when OFAC removed 274 individuals and entities associated with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or the FARC, from the SDN List.These entities and individuals had previously been designated under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions Regulations and the Global Terrorism Sanctions Regulations.However, according to the State Department, in acknowledgement of the fact that the FARC had formally dissolved and disarmed following the 2016 peace deal with the Colombian government, it “no longer exists as a unified organization that engages in terrorism or terrorist activity or has the capability or intent to do so.”

Another notable de-listing took place on February 16, 2021, when the State Department announced that it would be lifting the FTO and SDGT designations of the Yemen-based organization Ansarallah (commonly known as the Houthis) and its key leaders.The Houthis were designated just weeks earlier during the waning days of the Trump administration, triggering bipartisan concern about deepening the already significant practical challenges of delivering aid to the Yemeni people.This reversal, according to a State Department press release, came as “a recognition of the dire humanitarian situation in Yemen.”However,recent attacks by the Houthis against the United Arab Emirates—a close U.S. partner and host to a major U.S. military installation—have led some observers to suggest that the organization’s counter-terrorism designations should be reinstated.

In total, 787 persons and entities were removed from the SDN List during 2021, primarily as a result of the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Sanctions Regulations removals and the Narcotics Trafficking Sanctions Regulation removals.These removals appear to be in accord with the underlying policy rationale of sanctions designations—namely, to alter the behavior of malign actors.

During the past several years, the United States has increasingly used a novel and still evolving policy tool—controls on the information and communications technology and services (“ICTS”) supply chain—to shield sensitive U.S. data and communications.Years of malicious cyber activities targeting the United States have exposed both the significance of the ICTS industry to the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States and the vulnerabilities deep in the ICTS supply chain.Because a supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link, the ICTS supply chain controls regime seeks to identify the vulnerabilities down the supply chain to ensure the integrity of the ICTS industry.

The ICTS supply chain controls regime is built upon a number of Executive Orders—each addressing separate yet interrelated topics such as software applications, supply chain security, and cybersecurity—as well as accompanying regulations, reports, and initiatives by several government agencies, including the Department of Commerce and the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”).What results is an emerging regulatory regime that has the potential to bring about significant compliance challenges for global companies operating in the ICTS industry.Below we summarize the major developments from the past year.

A.Executive Order 13873:ICTS Supply Chain Framework

On May 15, 2019,acting under the authorities provided by the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—the statutory basis for most U.S. sanctions programs—then-President Trump issued Executive Order 13873 (the “ICTS E.O.”), declaring a national emergency with respect to the ability of foreign adversaries to create and exploit vulnerabilities in the ICTS supply chain.The ICTS E.O. charged the Commerce Department with implementing a new regulatory framework to control risks in the ICTS supply chain.Although the Commerce Department published a Proposed Rule pursuant to the ICTS E.O. in November 2019, there was not much movement in this new regulatory framework until the beginning of this year.

Just one day before the Biden administration’s start, on January 19, 2021, the Commerce Department published an Interim Final Rule establishing the processes and procedures that the Secretary of Commerce will use to evaluate ICTS transactions covered by the ICTS E.O.The Interim Final Rule provides the Department of Commerce with a broad, CFIUS-like authority to prohibit or unwind transactions or order mitigation measures.Specifically, it authorizes the Secretary of Commerce to prohibit ICTS transactions if the following three conditions are met:

First—The transactions must involve the acquisition, importation, transfer, installation, dealing in, or usage of certain ICTS.ICTS is broadly defined as any technology product or service used for the purpose of “information or data processing, storage, retrieval, or communication by electronic means, including transmission, storage, and display.”Despite many commenters’ requests to narrow the scope of the rules, the Commerce Department declined to provide categorical exemptions to specific industries or locations.Instead, the Commerce Department identified six main types of ICTS transactions that will fall under the scope of this rule, which include critical infrastructure, networks and satellites, data hosting or computing, surveillance or monitoring, communications software, and emerging technology.

Second—The ICTS must be designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by companies owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a “foreign adversary.”The Interim Final Rule identifies six specific “foreign adversaries”: (1) China, including the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; (2) Cuba; (3) Iran; (4) North Korea; (5) Russia; and (6) the Maduro regime of Venezuela.This list is subject to change, however—the Secretary of Commerce may revise the list to go into effect immediately without prior notice and comment.The “person owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a foreign adversary” may include:

Third—The ICTS transaction must “pose an undue or unacceptable risk”—an area that affords the Secretary of Commerce much discretion.The Interim Final Rule outlined broad criteria which the Secretary of Commerce may consider in assessing potential risks posed by the ICTS transaction:

Although the Interim Final Rule’s detailed lists of definitions and factors were an improvement from the 2019 Proposed Rule, the Interim Final Rule still left much room for discretion in the application of each of the three tests.Between the publication in January 2021 and the planned effective date in March, a number of U.S. trade associations submitted letters to the Commerce Department noting their concerns regarding the Rule’s sweeping scope and vague language and seeking to pause the Rule going into effect.Commentators also speculated as to the actions that the Biden administration might take to delay or reduce the impact of this midnight regulation from the prior administration.Despite the many doubts and unresolved questions, on March 22, 2021, the Interim Final Rule went into effect as planned.

Under the Interim Final Rule, the Secretary of Commerce may initiate a review of an ICTS transaction at his or her own discretion or upon written request from an appropriate agency head.If an ICTS transaction meets the criteria above, the Secretary of Commerce will make an initial determination as to whether to prohibit the ICTS transaction or propose mitigation measures.Within 30 days of receiving a notice of the Commerce determination, the parties may challenge the initial determination or propose remedial steps (such as corporate reorganization, disgorgement of control of the foreign adversary, or engagement of a compliance monitor).Upon review, the Commerce Department must issue a final determination stating whether the transaction is prohibited, not prohibited, or permitted subject to mitigation measures.The final determination is generally to be issued within 180 days of commencing the initial review.

This review process is similar to that of CFIUS—another tool that is designed to protect U.S. national security interests in transactions involving foreign entities.In fact, the Interim Final Rule exempts transactions that CFIUS is actively reviewing or has reviewed, possibly recognizing that the two set of reviews are intended to address similar risks.However, the Interim Final Rule warns “that CFIUS review related to a particular ICTS, by itself, does not present a safe harbor for future transactions involving the same ICTS that may present undue or unnecessary risks as determined by the [Commerce] Department.”Under the current construction, the Commerce Department can get a second chance to review a transaction even if CFIUS finds that it does not have jurisdiction or that the national security risks involved in the transaction are not significant.

To date, no transaction review has officially begun.However, the Commerce Department has made clear its intent to actively implement the Interim Final Rule.On March 17, 2021, the Commerce Department announced that it served subpoenas on multiple unnamed Chinese companies that provide ICTS in the United States.This announcement was coupled with an unequivocal statement from the Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo that the “Biden-Harris Administration has been clear that the unrestricted use of untrusted ICTS poses a national security risk” and that “Beijing has engaged in conduct that blunts our technological edge and threatens our allies.”On April 13, 2021, the Commerce Department followed up with another subpoena on an unnamed Chinese company.The fact that the only subpoenas served to date were to Chinese companies is telling—the scrutiny that CFIUS has shown toward transactions involving Chinese entities might hold true for the ICTS supply chain controls regime, as well.

The Interim Final Rule also suggested that the Commerce Department will set forth a procedure for parties to seek a license for a proposed or pending ICTS transaction.The license application review would be conducted on a fixed timeline, not to exceed 120 days from accepting an application, such that if the Department of Commerce does not issue a license decision within 120 days from accepting the application, it will be deemed granted.The Department of Commerce noted, however, that it would not issue a license decision on a transaction that would reveal sensitive information to foreign adversaries or others who may seek to undermine U.S. national security.

On March 29, 2021, the Commerce Department published a Proposed Rule seeking input on establishing licensing procedures for the ICTS supply chain controls regime, including a question concerning whether the licensing process should model that of a CFIUS notification or a voluntary disclosure to BIS.Unsurprisingly, the possibility of the Commerce Department going through license applications for countless ICTS transactions within 120 days garnered much concern regarding the practicality of such an arrangement.While the Commerce Department was slated to publish procedures for a licensing process by May 19, 2021, this did not happen, and the Commerce Department has not communicated a new timeline or specific plan to do so.

B.Executive Order 14034:Connected Software Applications

On June 9, 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 14034 (the “Applications E.O.”), which revoked three Trump-era Executive Orders that targeted by name TikTok and various other applications developed by Chinese companies.Instead, the Applications E.O. directed the Secretary of Commerce to undertake further consideration of the risks posed by “connected software applications” under the ICTS Supply Chain regulations, including potential undue or unacceptable risk to the ICTS, critical infrastructure, or national security of the United States.